Niels learns Rust 3 — Hello world!, global state, and flash memory

This is part 3 in my journey to learn Rust by porting my embedded Java virtual machine to it. Click here for the whole series.

After the last step we can compile Rust code for the target platform, the AVR family of embedded CPUs, specifically the ATmega128, and run the resulting binary in the Avrora AVR simulator. But it can’t print any output yet.

In this post I will add debug prints. I thought this would be an easy task, but it ended up taking many small steps, each of which taught me more about Rust.

Printing to console

In normal Rust, printing to the console is easy: println! prints to stdout and eprintln!() to stderr. For quick debugging dbg!() is very convenient: it returns the value passed to it, printing it to stderr in the process:

fn main() {

let a = 42;

let b = dbg!(a);

println!("b = {}", b);

}This will print:

[src/main.rs:3] a = 42

b = 42The first line is sent to stderr, the second to stdout.

However, I’m developing a VM for the AVR class of embedded processors. They don’t have an operating system, so there’s no stdout or stderr to write to. How can I print to see what my code is doing?

The CPU does have a UART that could be used to send output to, and using a physical board this could be a good idea. But in this case, the code will be running in the Avrora simulator, and this gives us another option: printing through a well defined memory location.

The c-print monitor

Avrora has several ‘monitors’ that can trace the execution of our code on the AVR. In the previous post I turned on the memory and stack monitors that keep track of memory accesses and guard the stack growth. Another monitor is called c-print, and it produces output by monitoring writes to a specific memory location.

The location being monitored is a single byte. For some operations this is enough. For example, writing 0x0E to it causes Avrora to print the contents of the CPU’s registers.

Others take a parameter, which is read from the next 2 or 4 bytes: writing 0x05 to the magic location prints the contents of the next 4 bytes as a unsigned 32 bit integer (little endian).

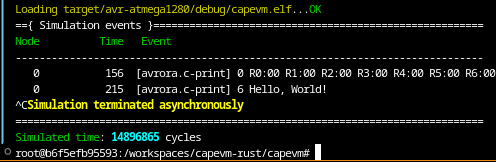

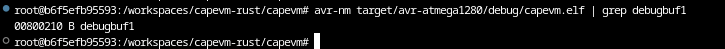

Avrora determines the memory location to monitor by searching for a specific symbol: debugbuf1.

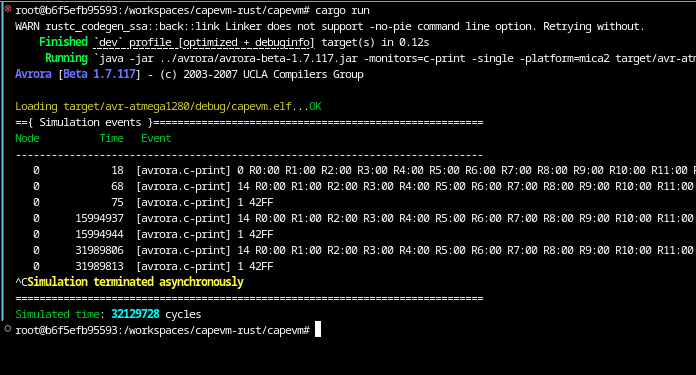

This output was taken from the finished code in this post. Avrora will monitor the byte at address 0x0210 and triggers the c-print monitor whenever our code writes to it.

Note the very high address shown in the output above. Being a Harvard architecture, the AVR has separate address spaces for code, which is in Flash memory, and RAM. The binutils toolchain wasn’t designed for this, and the avr version of it solves the problem by mapping RAM to addresses starting at 0x00800000, or 8 MB, far beyond the Flash capacity of any AVR CPU.

Global state in Rust

So we need a global variable we can write to. Programming 101 says global mutable state is bad, but sometimes there are valid reasons for it, and this is one.

How can we have global mutable state in Rust? Rust cares about safety, and global mutable state is inherently unsafe.

We can declare the variable as static mut debugbuf1: [u8; 5] = [0, 0, 0, 0, 0];. This works, but Rust has no way to guarantee its safety since anyone can touch it. Even though there’s no multithreaded OS on the AVR (there is, but not in this case), interrupts can cause all sorts of race conditions.

If Rust can’t prove the code to be safe, it wants us to be explicit about it, so while we can declare a static mut variable, the only way to access it is in an unsafe { ... } block.

std::sync::RwLock

The approach above is what I’ll use for the AVR, but since this blog is about learning Rust, I will sometimes take a little detour into something that may not work for this project, but is still worth learning about.

After searching around for a bit for articles about global state in Rust, I came across this little gem, which explains a lot of interesting things. I’ll have to get back to it and review it in detail, but one comment stood out:

There are safe patterns for global mutable singletons in Rust but those are outside the scope of this article.

This got me curious, what would those safe patterns be? A little more searching revealed two useful helper classes in the standard library: std::sync::Mutex<T> and std::sync::RwLock<T>.

The way to use them is pretty straightforward. Mutex is similar to RwLock but doesn’t distinguish between readers and writers. Here’s an example of how RwLock works:

use std::sync::RwLock;

static LOCK: RwLock<u8> = RwLock::new(5);

fn main() {

// many reader locks can be held at once

{

let r1 = LOCK.read().unwrap();

let r2 = LOCK.read().unwrap();

assert_eq!(*r1, 5);

assert_eq!(*r2, 5);

} // read locks are dropped at this point

// only one write lock may be held, however

{

let mut w = LOCK.write().unwrap();

*w += 1;

assert_eq!(*w, 6);

} // write lock is dropped at this point

// so we can get a new write lock in this block,

// but merging these two blocks into one would

// cause a deadlock

{

let mut w2 = LOCK.write().unwrap();

*w2 += 1;

assert_eq!(*w2, 7);

} //

println!("Done.");

}Try it on the Playground

We can wrap a resource in a RwLock, and get either multiple read-only references to it, or a single mutable reference.

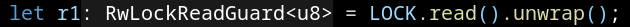

When we use VS Code, the type hints reveal we don’t just get a reference to a u8 (either a &u8 or a mutable &mut u8) when we call read() or write(), but a RwLockReadGuard<u8> or RwLockWriteGuard<u8>:

Again, the nice thing about Rust is that you can easily have a look at the implementation.

The exact details of the implementation are still a bit beyond me, but it’s clear they both implement the Deref<T> trait (where T is u8), which is why Rust lets us implicitly coerce them to a &u8. In addition the write guard also implements DeferMut<T>, so we can coerce that to a &mut u8 as well.

In the same file we can also see they both implement the Drop trait, and the drop() functions call read_unlock() or write_unlock() to release the lock. Rust will drop any value as soon as it goes out of scope, which is why the w lock is release at the end of the middle block. Merging the two blocks would cause a deadlock, unless we add an explicit drop(w); before asking for the second write lock.

The implementations of these traits are all unsafe { } code, which is a bit of a misnomer since it’s not actually unsafe. What unsafe means is in fact “unverified”: the compiler can’t be sure the code is safe, but if it is, any code using it will be as well.

It’s important to note though, that while this code is safe in the sense that they avoid race conditions — as long as we hold either lock, we can be sure no one else modifies the locked data — they don’t prevent deadlocks and certainly don’t have to be fast since waiting for a lock to be released can easily become a performance bottleneck. Shared state is always messy.

libcore and libstd

This seemed like a good alternative to avoid unsafe code, but unfortunately we can’t use it on the AVR. The reason is the first line of the code that was generated by the template we used: #![no_std] (the ! indicates the attribute applies to the entire crate).

The no_std tells Rust not to link to the std crate, so anything in std:: isn’t available. Only the core crate will be available.

The documentation explains this quite clearly: there are two main crates, libcore and libstd. The first, libcore, is always available and contains things like the primitive types, basic language constructs sure as Option<T>, Result<T,E>, assert, etc.:

The Rust Core Library is the dependency-free foundation of The Rust Standard Library. It is the portable glue between the language and its libraries, defining the intrinsic and primitive building blocks of all Rust code. It links to no upstream libraries, no system libraries, and no libc. The core library is minimal: it isn’t even aware of heap allocation, nor does it provide concurrency or I/O. These things require platform integration, and this library is platform-agnostic.

The second, libstd, is much larger and contains many constructs that rely on an operating system. It is a superset of libcore, which we can see by looking at the source in std/src/lib.rs:

#[stable(feature = "rust1", since = "1.0.0")]

pub use core::any;

#[stable(feature = "core_array", since = "1.36.0")]

pub use core::array;

#[unstable(feature = "async_iterator", issue = "79024")]

pub use core::async_iter;

...This is a common pattern in Rust: pub use imports features from another crate or module, and exports them again in the current. In short, everything that’s exported by libcore, is also exported by libstd.

Knowing this, it makes sense RwLock lives in libstd, since it must depend on some operating system primitives to guarantee atomicity and safety. Unfortunately, we don’t have an OS on the AVR, so it only has access to libcore and RwLock is of no use for this project.

Global state on the AVR

Since we can’t use RwLock<T>, we have to use a static mut debugbuf1 variable. Let’s first consider a simple opcode without parameters that will print all registers.

A first attempt might look like this:

#[allow(non_upper_case_globals)]

static mut debugbuf1: u8 = 0;

const AVRORA_PRINT_REGS: u8 = 0xE;

#[arduino_hal::entry]

fn main() -> ! {

loop {

unsafe {

debugbuf1 = AVRORA_PRINT_REGS;

}

arduino_hal::delay_ms(1000);

}

}The #[allow(non_upper_case_globals)] suppresses a warning because Rust likes globals to have upper case names.

To test it, add the c-print monitor to .cargo/config.toml and remove the others:

[target.'cfg(target_arch = "avr")']

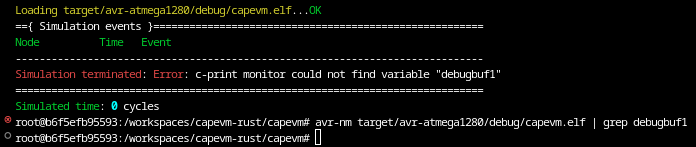

runner = "java -jar ../avrora/avrora-beta-1.7.117.jar -monitors=c-print -single -platform=mica2"Unfortunately, this doesn’t work:

Avrora can’t find the name debugbuf1 because from Rust’s point of view, no one ever reads from it and the optimiser removed it completely. We need an equivalent of C’s volatile keyword.

Luckily Rust has a function to do precisely that:

pub unsafe fn write_volatile<T>(dst: *mut T, src: T)Performs a volatile write of a memory location with the given value without reading or dropping the old value.

Volatile operations are intended to act on I/O memory, and are guaranteed to not be elided or reordered by the compiler across other volatile operations.

It needs a *mut instead of a &mut: a raw pointer instead of a reference. Raw pointers are essentially C pointers, and dereferencing them is unsafe.

Initially I tried this, since a &T reference can be implicitly coerced to a *T raw pointer. Using the raw pointer is unsafe, but just creating it is not.

use core::ptr::write_volatile;

#[allow(non_upper_case_globals)]

static mut debugbuf1: u8 = 0;

const AVRORA_PRINT_REGS: u8 = 0xE;

#[arduino_hal::entry]

fn main() -> ! {

loop {

unsafe {

write_volatile(&mut debugbuf1, AVRORA_PRINT_REGS);

}

arduino_hal::delay_ms(1000);

}

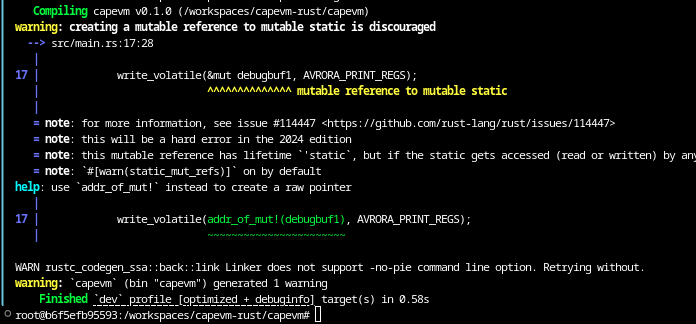

}It compiles, but Rust is still a little unhappy:

References to static data result in a warning in recent Rust compilers, and will become an error in the 2024 language edition (see this issue on github). As usual, the compiler is quite helpful in telling us how to fix things: addr_of_mut!() gives us a raw pointer to a mutable without first having to create a reference.

I suppose the idea is that forcing the developer to work with raw pointers makes it more explicit that mutable static data is inherently unsafe and requires extra care.

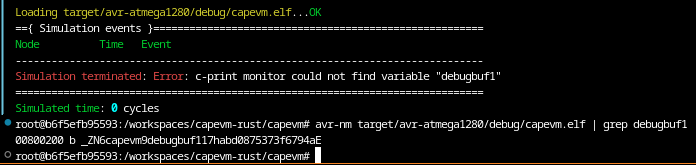

This helps, and the code now compiles without warning, but Avrora still can’t find it:

Rust mangles symbols names to make sure they’re unique in the resulting binary, even if two blocks use the same name to define a static. We can add the #[no_mangle] attribute to prevent this (which has a number of other effects beyond just preventing the compiler from mangling the name).

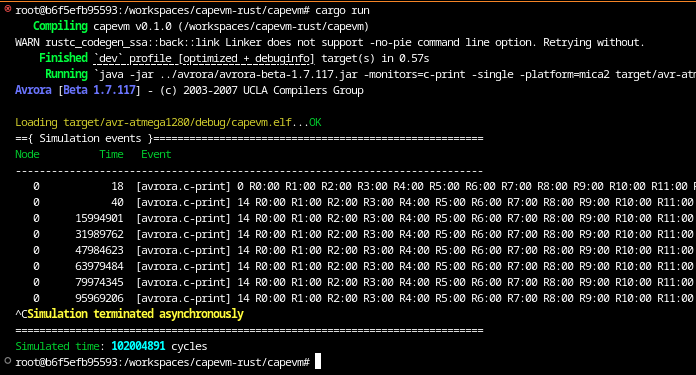

It works, we finally have some (still rather boring) output!

Passing parameters to Avrora

The c-print monitor has a number of debug print commands that don’t need any parameters to print registers, or even the heap contents in the VM. Others commands take a parameter of 2 or 4 bytes, so let’s extend the static we defined before and print a 16 bit value as hex:

#[no_mangle]

#[allow(non_upper_case_globals)]

static mut debugbuf1: [u8; 5] = [0, 0, 0, 0, 0];

const AVRORA_PRINT_2BYTE_HEXADECIMALS: u8 = 0x1;

const AVRORA_PRINT_REGS: u8 = 0xE;

#[arduino_hal::entry]

fn main() -> ! {

loop {

unsafe {

write_volatile(addr_of_mut!(debugbuf1[0]), AVRORA_PRINT_REGS);

let val = 0x42FF;

write_volatile(addr_of_mut!(debugbuf1[1]), val as u8);

write_volatile(addr_of_mut!(debugbuf1[2]), (val >> 8) as u8);

write_volatile(addr_of_mut!(debugbuf1[0]), AVRORA_PRINT_2BYTE_HEXADECIMALS);

}

arduino_hal::delay_ms(1000);

}

}

The output is a bit raw, but it works perfectly.

Strangely, with debugbuf1 now a 5-byte array, the compiler stopped giving the warning we saw before we added addr_of_mut!. We can write directly to &mut debugbuf1[0] without warning.

This confused me for a while, but asking around on Stack Overflow revealed this is a limitation in the linter that looks like it will be fixed soon, so we should still keep using addr_of_mut!.

The other variants for signed and unsigned 8, 16 or 32 bit values follow the same pattern.

The ‘avrora’ module

When developing the VM, we don’t want to be copying these lines over and over again. It would be much nicer to have a module with convenient functions for all of the interactions we will have with the simulator (various tracing calls will be added later). So let’s make one.

We can make a module by simply creating a file called either avrora.rs or avrora/mod.rs. Including some refactoring that will make it easier to add the other kinds of print commands, it looks like this:

use core::ptr::{addr_of_mut, write_volatile};

const AVRORA_PRINT_2BYTE_HEXADECIMALS: u8 = 0x1;

const AVRORA_PRINT_REGS: u8 = 0xE;

#[allow(non_upper_case_globals)]

#[no_mangle]

static mut debugbuf1: [u8; 5] = [0, 0, 0, 0, 0];

fn signal_avrora_c_print(instruction: u8) {

unsafe {

write_volatile(addr_of_mut!(debugbuf1[0]), instruction);

}

}

fn signal_avrora_c_print_16(instruction: u8, payload: u16) {

unsafe {

write_volatile(addr_of_mut!(debugbuf1[1]), payload as u8);

write_volatile(addr_of_mut!(debugbuf1[2]), (payload >> 8) as u8);

write_volatile(addr_of_mut!(debugbuf1[0]), instruction);

}

}

/// Uses Avrora's c-print monitor to print a 16 bit unsigned int as hex

#[allow(dead_code)]

pub fn print_u16_hex(val: u16) {

signal_avrora_c_print_16(AVRORA_PRINT_2BYTE_HEXADECIMALS, val);

}

/// Uses Avrora's c-print monitor to print the contents of the registers R0 to R31

#[allow(dead_code)]

pub fn print_all_regs() {

signal_avrora_c_print(AVRORA_PRINT_REGS);

}The allow(dead_code) is necessary to prevent the compiler from complaining when we don’t use a particular debug print. The code won’t be included in the final binary if it’s not used.

With this, the main file becomes nice and clean, and free of any unsafe code:

#![no_std]

#![no_main]

use panic_halt as _;

mod avrora;

#[arduino_hal::entry]

fn main() -> ! {

loop {

avrora::print_all_regs();

avrora::print_u16_hex(0x42FF);

arduino_hal::delay_ms(1000);

}

}Further extending the module to print 8, 16 and 32 bit signed or unsigned numbers is straightforward, but printing strings requires some special tricks.

Hello, World! (finally)

Avrora’s c-print monitor has several ways to print strings. The easiest is quite straightforward:

/// Uses Avrora's c-print monitor to print a string from RAM

#[allow(dead_code)]

pub fn print_ram_string(s: &str) {

signal_avrora_c_print_16(AVRORA_PRINT_STRING_POINTERS, s.as_ptr() as u16);

}We pass a reference to a string slice, take the address using .as_ptr() and cast this to a 16 bit int to use as the parameter for the monitor call.

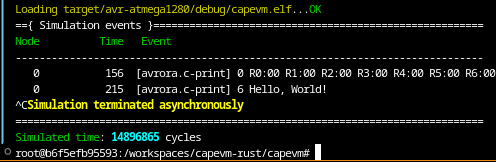

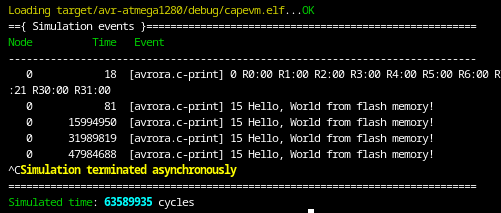

This allows us to do avrora::print_ram_str("Hello, world!"); in main.rs, and finally gives us a working “Hello, world!”: 🎉🎉🎉

However, there’s a problem with this approach:

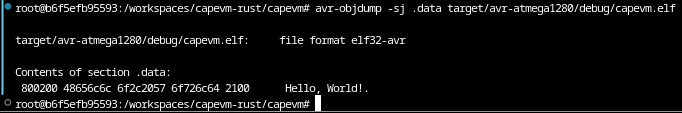

Rust placed the string in the .data section, which sits in RAM. On most platforms this would be fine, but on the AVR, RAM is a very scarce resource. The ATmega128 only has 4 KB of RAM, but 128 KB flash memory. Code is executed from flash, data is normally stored in RAM, but if the data is constant, we would prefer to store it in flash as well.

There is a small performance penalty for reading from flash memory on the AVR: LPM, for Load Program Memory, takes 3 cycles compared to 1 or two for a normal LD load from RAM. But in this case that doesn’t matter since the string will only be read by the simulator, not by the device itself.

The call to print from flash is almost identical, but with a different command and a 32 bit address since the flash address range is larger:

/// Uses Avrora's c-print monitor to print a string from flash memory

#[allow(dead_code)]

pub fn print_flash_string(addr: u32) {

signal_avrora_c_print_32(AVRORA_PRINT_FLASH_STRING_POINTER, addr);

}But how do we get the string into flash? Luckily there’s a crate called avr_progmem to do this.

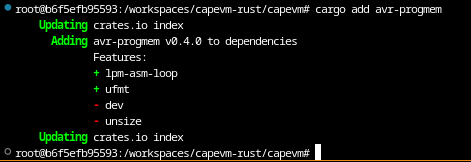

First, install it using Cargo:

This gives us a new macro, progmem!, that can be used to place data in flash. The crate also offers convenient ways to read from flash memory without having to resort to assembly that may come in handy later. With it, we can put data in flash like this:

progmem! {

static progmem string HELLO = "Hello, World!\0";

}

avrora::print_flash_string(HELLO.as_bytes().as_ptr() as u32);The static HELLO becomes a PmString<_>, from which we can a reference to the bytes as &ProgMem<[u8; _]>, from which we can get a raw *const T pointer, that can be cast to a u32 containing the address. The \0 is necessary to terminate the string since Avrora expects a null-terminated string. Without it, it will print garbage until it encounters the first \0.

The print_flash_string macro.

This works, but is quite verbose for just a debug print. It would be nice if we could just write avrora::print_flash_string("Hello, World!").

We can’t using do this normal Rust functions, but we can achieve almost the same with a macro:

/// Uses Avrora's c-print monitor to print a string from flash memory

#[allow(unused_macros)]

#[macro_export]

macro_rules! print_flash_string {

($s:expr) => { {

use avr_progmem::progmem;

progmem! {

static progmem string AVRORA_PROGMEMSTRING = concat!($s, "\0");

}

avrora::print_flash_string_fn(AVRORA_PROGMEMSTRING);

} };

}

/// Uses Avrora's c-print monitor to print a string from flash memory

///

/// This should be called by the print_flash_string! macro, which can

/// conveniently store a string in flash memory and create the

/// required PmString.

#[allow(dead_code)]

pub fn print_flash_string_fn<const N: usize>(string_in_progmem: PmString<N>) {

signal_avrora_c_print_32(

AVRORA_PRINT_FLASH_STRING_POINTER,

string_in_progmem.as_bytes().as_ptr() as u32);

}There is a lot to learn about macros, but so far I only skipped ahead in ‘Programming Rust’ to the macro chapter to learn just enough to make this work.

Rust’s macros are executed very early on in the compilation process, which is the reason we have to #[macro_export] them instead of declaring them pub as for functions. The whole concept of pub has no meaning yet at this stage in the compilation process. Unfortunately that also means we can’t access them through avrora:: as we did for the others.

They work on the token stream rather than on plain text as in C. Macro definitions contain one or more cases that are matched in a regex-like way. The macro is then expanded to the corresponding body.

Macros capture parts of the token stream, qualified by a ‘designator’ to indicate what kind of tokens the macro expects. Here, ($s:expr) matches a single expression and stores it in $s.

The print_flash_string macro then expands to a block that first defines a static AVRORA_PROGMEMSTRING in progmem, and calls the print_flash_string function to print it.

Note the double curly braces: { { ... } }. The outer braces delimit the expansion of macro case and are not included in the resulting code. The inner braces turn the expansion of the macro into a new block instead of expanding directly into the code where the macro is used.

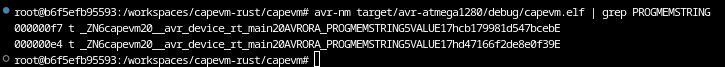

Why is this important? Without the extra braces, two print statements in a row would defined two AVRORA_PROGMEMSTRING statics in the same block, and the names would collide. By wrapping the generated code in braces, they no longer conflict, and Rust’s name mangling makes sure they will have unique symbols in the final binary:

We can now use the macro almost like the other print functions:

print_flash_string!("Hello, World from flash memory!");

The only difference is that macro are directly available in the namespace and can’t be prefixed with avrora::, which is a pity because for a new developer just typing avrora:: and seeing what pops up in the IDE makes it easy to find out what options are available.

This was the main reason to keep the names of the macro and function the same and have the triple slash documentation on the function direct the user to the corresponding macro.

Note also that the macro is expanded in the code where it is used, which means it does not have access to the private functions in the avrora module. So we need some public entrypoint exposed for the macro to call and this seemed the cleanest way to do so.

EDIT 2024-05-16

Since this is a learning project, sometimes you realise you get things wrong. Well that didn’t take long.

The first version of the macro worked, but the fact that the call couldn’t be prefixed with avrora:: felt a bit wrong, and when I wanted to use it from another module, I discovered the macro needed to be imported separately as use avrora::print_flash_string. Yuck.

It turns out there are two better ways to make the macro available to other modules. First, I could have replaced the mod avrora in my main.rs with this:

#[macro_use]

mod avrora;This makes the macro available in all the modules in the crate. But it still ends up in the global namespace, while I would prefer to be able to have it under avrora:: with all the other print functions. The way to do this is to add the following lines in the avrora module, which exports it along with the pub functions to anyone who imports the module.

// Export the macro so it can be used as 'avrora::print_flash_string!'

#[allow(unused_imports)]

pub(crate) use print_flash_string;It feels a bit odd to have to use something in the module it is defined in. To be honest, this part of Rust feels like the design changed a few times and some old options had to be maintained for backwards compatibility. Note also that the macro is expanded in the code where it is used, so it does not have access to the private functions in the avrora module. This means we need some public entrypoint exposed for the macro to call, which is why there is an accompanying print_flash_string_fn function.

Now it works the way I want it to work, and we can call print_flash_string scoped to the avrora module so it can be easily found:

avrora::print_flash_string!("Hello, World from flash memory!");Recap

This took quite a few more steps than I anticipated, but it taught me a lot of interesting things:

dbg!static mutdata andunsafecodeRwLock- How stdcore and stdlib relate

write_volatileandaddr_of_mut- The

no_mangleattribute - Creating a module

- How to suppress warnings where appropriate

- Raw pointers

- Using avr_progmem to put data in flash memory

- How to write a simple macro

As usual the state of the code at the end of this step can be found here on Github.

Tags: [rust]